Factitious disorder imposed on another – Wikipedia

Factitious disorder imposed on anotherOther namesFactitious disorder by proxy, Munchausen syndrome by proxy (MSbP, MbP), fabricated or induced illness by carers (FII), medical child abuseOverview of factitious disorder imposed on anotherSpecialtyPsychiatrySymptomsVariable[1]CausesUnknown[2]Risk factorsPregnancy related complications, caregiver who was abused as a child or has factitious disorder imposed on self[3]Diagnostic methodRemoving the child from the caregiver results in improvement, video surveillance without the knowledge of the caregiver[4]Differential diagnosisMedical disorder, other forms of child abuse, delusional disorder[5]TreatmentRemoval of the child, therapy[2][4]FrequencyRare, estimated 1 to 28 per million children[6]

Factitious disorder imposed on another (FDIA), also called Munchausen syndrome by proxy (MSbP), is a condition in which a caregiver creates the appearance of health problems in another person, typically their child. [7] This may include injuring the child or altering test samples. [7] They then present the person as being sick or injured. [5] The behaviour occurs without a specific benefit to the caregiver. [5] Permanent injury or death may occur as a result of the disorder. [7]

The cause of FDIA is unknown. [2] The primary motive may be to gain attention and manipulate physicians. [4] Risk factors for FDIA include pregnancy related complications and a mother who was abused as a child or has factitious disorder imposed on self. [3] Diagnosis is supported when removing the child from the caregiver results in improvement of symptoms or video surveillance without the knowledge of the caregiver finds concerns. [4] Those affected by the disorder have been subjected to a form of physical abuse and medical neglect. [1]

Management of FDIA may require putting the child in foster care. [2][4] It is not known how effective therapy is for FDIA; it is assumed it may work for those who admit they have a problem. [4] The prevalence of FDIA is unknown, [5] but it appears to be relatively rare. [4] More than 95% of cases involve a person’s mother. [3]

The prognosis for the caregiver is poor. [4] However, there is a burgeoning literature on possible courses of therapy. [3]

The condition was first named, as “Munchausen syndrome by proxy”, in 1977 by British paediatrician Roy Meadow. [4] Some aspects of FDIA may represent criminal behavior. [5]

Signs and symptoms[edit]

In factitious disorder imposed on another, a caregiver makes a dependent person appear mentally or physically ill in order to gain attention. To perpetuate the medical relationship, the caregiver systematically misrepresents symptoms, fabricates signs, manipulates laboratory tests, or even purposely harms the dependent (e. g. by poisoning, suffocation, infection, physical injury). [6] Studies have shown a mortality rate of between six and ten percent, making it perhaps the most lethal form of abuse. [8][9]

In one study, the average age of the affected individual at the time of diagnosis was 4 years old. Slightly over 50% were aged 24 months or younger, and 75% were under six years old. The average duration from onset of symptoms to diagnosis was 22 months. By the time of diagnosis, six percent of the affected persons were dead, mostly from apnea (a common result of smothering) or starvation, and seven percent had long-term or permanent injury. About half of the affected had siblings; 25% of the known siblings were dead, and 61% of siblings had symptoms similar to the affected or that were otherwise suspicious. The mother was the perpetrator in 76. 5% of the cases, the father in 6. 7%. [9]

Most present about three medical problems in some combination of the 103 different reported symptoms. The most-frequently reported problems are apnea (26. 8% of cases), anorexia or feeding problems (24. 6% of cases), diarrhea (20%), seizures (17. 5%), cyanosis (blue skin) (11. 7%), behavior (10. 4%), asthma (9. 5%), allergy (9. 3%), and fevers (8. 6%). [9] Other symptoms include failure to thrive, vomiting, bleeding, rash, and infections. [8][10] Many of these symptoms are easy to fake because they are subjective. A parent reporting that their child had a fever in the past 24 hours is making a claim that is impossible to prove or disprove. The number and variety of presented symptoms contribute to the difficulty in reaching a proper diagnosis.

Aside from the motive (most commonly attributed to be a gain in attention or sympathy), another feature that differentiates FDIA from “typical” physical child abuse is the degree of premeditation involved. Whereas most physical abuse entails lashing out at a child in response to some behavior (e. g., crying, bedwetting, spilling food), assaults on the FDIA victim tend to be unprovoked and planned. [11]

Also unique to this form of abuse is the role that health care providers play by actively, albeit unintentionally, enabling the abuse. By reacting to the concerns and demands of perpetrators, medical professionals are manipulated into a partnership of child maltreatment. [6] Challenging cases that defy simple medical explanations may prompt health care providers to pursue unusual or rare diagnoses, thus allocating even more time to the child and the abuser. Even without prompting, medical professionals may be easily seduced into prescribing diagnostic tests and therapies that are at best uncomfortable and costly, and at worst potentially injurious to the child. [1] If the health practitioner resists ordering further tests, drugs, procedures, surgeries, or specialists, the FDIA abuser makes the medical system appear negligent for refusing to help a sick child and their selfless parent. [6] Like those with Munchausen syndrome, FDIA perpetrators are known to switch medical providers frequently until they find one that is willing to meet their level of need; this practice is known as “doctor shopping” or “hospital hopping”.

The perpetrator continues the abuse because maintaining the child in the role of patient satisfies the abuser’s needs. The cure for the victim is to separate the child completely from the abuser. When parental visits are allowed, sometimes there is a disastrous outcome for the child. Even when the child is removed, the perpetrator may then abuse another child: a sibling or other child in the family. [6]

Factitious disorder imposed on another can have many long-term emotional effects on a child. Depending on their experience of medical interventions, a percentage of children may learn that they are most likely to receive the positive parental attention they crave when they are playing the sick role in front of health care providers. Several case reports describe Munchausen syndrome patients suspected of themselves having been FDIA victims. [12] Seeking personal gratification through illness can thus become a lifelong and multi-generational disorder in some cases. [6] In stark contrast, other reports suggest survivors of FDIA develop an avoidance of medical treatment with post-traumatic responses to it. [13]

The adult caregiver who has abused the child often seems comfortable and not upset over the child’s hospitalization. While the child is hospitalized, medical professionals must monitor the caregiver’s visits to prevent an attempt to worsen the child’s condition. [14] In addition, in many jurisdictions, medical professionals have a duty to report such abuse to legal authorities. [15]

Diagnosis[edit]

Munchausen syndrome by proxy is a controversial term. In the World Health Organization’s International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10), the official diagnosis is factitious disorder (301. 51 in ICD-9, F68. 12 in ICD-10). Within the United States, factitious disorder imposed on another (FDIA or FDIoA) was officially recognized as a disorder in 2013, [5] while in the United Kingdom, it is known as fabricated or induced illness by carers (FII). [16]

In DSM-5, the diagnostic manual published by the American Psychiatric Association in 2013, this disorder is listed under 300. 19 Factitious disorder. This, in turn, encompasses two types:[5]

Factitious disorder imposed on self – (formerly Munchausen syndrome).

Factitious disorder imposed on another – (formerly Munchausen syndrome by proxy); diagnosis assigned to the perpetrator; the person affected may be assigned an abuse diagnosis (e. child abuse).

Warning signs[edit]

Warning signs of the disorder include:[14]

A child who has one or more medical problems that do not respond to treatment or that follow an unusual course that is persistent, puzzling, and unexplained.

Physical or laboratory findings that are highly unusual, discrepant with patient’s presentation or history, or physically or clinically impossible.

A parent who appears medically knowledgeable, fascinated with medical details and hospital gossip, appears to enjoy the hospital environment, and expresses interest in the details of other patients’ problems.

A highly attentive parent who is reluctant to leave their child’s side and who themselves seem to require constant attention.

A parent who appears unusually calm in the face of serious difficulties in their child’s medical course while being highly supportive and encouraging of the physician, or one who is angry, devalues staff, and demands further intervention, more procedures, second opinions, and transfers to more sophisticated facilities.

The suspected parent may work in the health-care field themselves or profess an interest in a health-related job.

The signs and symptoms of a child’s illness may lessen or simply vanish in the parent’s absence (hospitalization and careful monitoring may be necessary to establish this causal relationship).

A family history of similar or unexplained illness or death in a sibling.

A parent with symptoms similar to their child’s own medical problems or an illness history that itself is puzzling and unusual.

A suspected emotionally distant relationship between parents; the spouse often fails to visit the patient and has little contact with physicians even when the child is hospitalized with a serious illness.

A parent who reports dramatic, negative events, such as house fires, burglaries, or car accidents, that affect them and their family while their child is undergoing treatment.

A parent who seems to have an insatiable need for adulation or who makes self-serving efforts for public acknowledgment of their abilities.

A child who inexplicably deteriorates whenever discharge is planned.

A child that looks for cueing from a parent in order to feign illness when medical personnel are present.

A child that is overly articulate regarding medical terminology and their own disease process for their age.

A child that presents to the Emergency Department with a history of repeat illness, injury, or hospitalization.

Epidemiology[edit]

FDIA is rare. Incidence rate estimates range from 1 to 28 per million children, [6] although some assume that it may be much more common. [6]

One study showed that in 93 percent of FDIA cases, the abuser is the mother or another female guardian or caregiver. [11] A psychodynamic model of this kind of maternal abuse exists. [17]

Fathers and other male caregivers have been the perpetrators in only seven percent of the cases studied. [9] When they are not actively involved in the abuse, the fathers or male guardians of FDIA victims are often described as being distant, emotionally disengaged, and powerless. These men play a passive role in FDIA by being frequently absent from the home and rarely visiting the hospitalized child. Usually, they vehemently deny the possibility of abuse, even in the face of overwhelming evidence or their child’s pleas for help. [6][11]

Overall, male and female children are equally likely to be the victim of FDIA. In the few cases where the father is the perpetrator, however, the victim is three times more likely to be male. [9]

One study in Italy found that 4 out of more than 700 children admitted to the hospital met the criteria (0. 53%). In this study, stringent diagnostic criteria were used, which required at least one test outcome or event that could not possibly have occurred without deliberate intervention by the FDIA person. [18]

Society and culture[edit]

Terminology[edit]

The term “Munchausen syndrome by proxy”, in the United States, has never officially been included as a discrete mental disorder by the American Psychiatric Association, [19] which publishes the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), now in its fifth edition. [5] Although the DSM-III (1980) and DSM-III-R (1987) included Munchausen syndrome, they did not include MSbP. DSM-IV (1994) and DSM-IV-TR (2000) added MSbP as a proposal only, and although it was finally recognized as a disorder in DSM-5 (2013), each of the last three editions of the DSM designated the disorder by a different name.

FDIA has been given different names in different places and at different times. What follows is a partial list of alternative names that have been either used or proposed (with approximate dates):[16]

Factitious Disorder Imposed on Another (current) (U. S., 2013) American Psychiatric Association, DSM-5

Factitious Disorder by Proxy (FDP, FDbP) (proposed) (U. S., 2000) American Psychiatric Association, DSM-IV-TR[20]

Fictitious Disorder by Proxy (FDP, FDbP) (proposed) (U. S., 1994) American Psychiatric Association, DSM-IV

Fabricated or Induced Illness by Carers (FII) (U. K., 2002) The Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health[21]

Factitious Illness by Proxy (1996) World Health Organization[22]

Pediatric Condition Falsification (PCF) (proposed) (U. S., 2002) American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children proposed this term to diagnose the victim (child); the perpetrator (caregiver) would be diagnosed “factitious disorder by proxy”; MSbP would be retained as the name applied to the ‘disorder’ that contains these two elements, a diagnosis in the child and a diagnosis in the caretaker. [23]

Induced Illness (Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy) (Ireland, 1999–2002) Department of Health and Children[16]

Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy (2002) Professor Roy Meadow. [16][4]

Meadow’s Syndrome (1984–1987) named after Roy Meadow. [24] This label, however, had already been in use since 1957 to describe a completely unrelated and rare form of cardiomyopathy. [25]

Polle Syndrome (1977–1984) coined by Burman and Stevens, from the then-common belief that Baron Münchhausen’s second wife gave birth to a daughter named Polle during their marriage. [26][27] The baron declared that the baby was not his, and the child died from “seizures” at the age of 10 months. The name fell out of favor after 1984, when it was discovered that Polle was not the baby’s name, but rather was the name of her mother’s hometown. [28][29]

While it initially included only the infliction of harmful medical care, the term has subsequently been extended to include cases in which the only harm arose from medical neglect, noncompliance, or even educational interference. [1] The term is derived from Munchausen syndrome, a psychiatric factitious disorder wherein those affected feign disease, illness, or psychological trauma to draw attention, sympathy, or reassurance to themselves. [30] Munchausen syndrome by proxy perpetrators, by contrast, are willing to fulfill their need for positive attention by hurting their own child, thereby assuming the sick role onto their child, by proxy. These proxies then gain personal attention and support by taking on this fictitious “hero role” and receive positive attention from others, by appearing to care for and save their so-called sick child. [6] They are named after Baron Munchausen, a literary character based on Hieronymus Karl Friedrich, Freiherr von Münchhausen (1720–1797), a German nobleman and well-known storyteller. In 1785, writer and con artist Rudolf Erich Raspe anonymously published a book in which a fictional version of “Baron Munchausen” tells fantastic and impossible stories about himself, establishing a popular literary archetype of a bombastic exaggerator. [31][32]

Initial description[edit]

“Munchausen syndrome” was first described by R. Asher in 1951[33] as when someone invents or exaggerates medical symptoms, sometimes engaging in self-harm, to gain attention or sympathy.

The term “Munchausen syndrome by proxy” was first coined by John Money and June Faith Werlwas in a 1976 paper titled Folie à deux in the parents of psychosocial dwarfs: Two cases[34][35] to describe the abuse-induced and neglect-induced symptoms of the syndrome of abuse dwarfism. That same year, Sneed and Bell wrote an article titled The Dauphin of Munchausen: factitious passage of renal stones in a child. [36]

According to other sources, the term was created by the British pediatrician Roy Meadow in 1977. [28][37][38] In 1977, Roy Meadow – then professor of pediatrics at the University of Leeds, England – described the extraordinary behavior of two mothers. According to Meadow, one had poisoned her toddler with excessive quantities of salt. The other had introduced her own blood into her baby’s urine sample. This second case occurred during a series of Outpatient visits to the Paediatric Clinic of Dr. Bill Arrowsmith at Doncaster Royal Infirmary. He referred to this behavior as Munchausen syndrome by proxy (MSbP). [39]

The medical community was initially skeptical of FDIA’s existence, but it gradually gained acceptance as a recognized condition.

Controversy[edit]

During the 1990s and early 2000s, Roy Meadow was an expert witness in several murder cases involving MSbP/FII. Meadow was knighted for his work for child protection, though later, his reputation, and consequently the credibility of MSbP, became damaged when several convictions of child killing, in which he acted as an expert witness, were overturned. The mothers in those cases were wrongly convicted of murdering two or more of their children, and had already been imprisoned for up to six years. [40][38]

One case was that of Sally Clark. Clark was a lawyer wrongly convicted in 1999 of the murder of her two baby sons, largely on the basis of Meadow’s evidence. As an expert witness for the prosecution, Meadow asserted that the odds of there being two unexplained infant deaths in one family were one in 73 million. That figure was crucial in sending Clark to jail but was hotly disputed by the Royal Statistical Society, who wrote to the Lord Chancellor to complain. [41] It was subsequently shown that the true odds were much lower once other factors (e. genetic or environmental) were taken into consideration, meaning that there was a significantly higher likelihood of two deaths happening as a chance occurrence than Meadow had claimed during the trial. Those odds in fact range from a high of 1:8500 to as low as 1:200. [42] It emerged later that there was clear evidence of a Staphylococcus aureus infection that had spread as far as the child’s cerebrospinal fluid. [43] Clark was released in January 2003 after three judges quashed her convictions in the Court of Appeal in London, [43][44] but suffering from catastrophic trauma of the experience, she later died from alcohol poisoning. Meadow was involved as a prosecution witness in three other high-profile cases resulting in mothers being imprisoned and subsequently cleared of wrongdoing: Trupti Patel, [45] Angela Cannings[46] and Donna Anthony. [47]

In 2003, Lord Howe, the Opposition spokesman on health, accused Meadow of inventing a “theory without science” and refusing to produce any real evidence to prove that Munchausen syndrome by proxy actually exists. It is important to distinguish between the act of harming a child, which can be easily verified, and motive, which is much harder to verify and which FDIA tries to explain. For example, a caregiver may wish to harm a child out of malice and then attempt to conceal it as illness to avoid detection of abuse, rather than to draw attention and sympathy.

The distinction is often crucial in criminal proceedings, in which the prosecutor must prove both the act and the mental element constituting a crime to establish guilt. In most legal jurisdictions, a doctor can give expert witness testimony as to whether a child was being harmed but cannot speculate regarding the motive of the caregiver. FII merely refers to the fact that illness is induced or fabricated and does not specifically limit the motives of such acts to a caregiver’s need for attention and/or sympathy.

In all, around 250 cases resulting in conviction in which Meadow was an expert witness were reviewed, with few[citation needed] changes, but all where the only evidence was Meadow’s expert testimony were overturned. Meadow was investigated by the British General Medical Council (GMC) over evidence he gave in the Sally Clark trial. In July 2005, the GMC declared Meadow guilty of “serious professional misconduct”, and he was struck off the medical register for giving “erroneous” and “misleading” evidence. [48]

At appeal, High Court judge Mr. Justice Collins said that the severity of his punishment “approaches the irrational” and set it aside. [49][50]

Collins’s judgment raises important points concerning the liability of expert witnesses – his view is that referral to the GMC by the losing side is an unacceptable threat and that only the Court should decide whether its witnesses are seriously deficient and refer them to their professional bodies. [51]

In addition to the controversy surrounding expert witnesses, an article appeared in the forensic literature that detailed legal cases involving controversy surrounding the murder suspect. [52] The article provides a brief review of the research and criminal cases involving Munchausen syndrome by proxy in which psychopathic mothers and caregivers were the murderers. It also briefly describes the importance of gathering behavioral data, including observations of the parents who commit the criminal acts. The article references the 1997 work of Southall, Plunkett, Banks, Falkov, and Samuels, in which covert video recorders were used to monitor the hospital rooms of suspected FDIA victims. In 30 out of 39 cases, a parent was observed intentionally suffocating their child; in two they were seen attempting to poison a child; in another, the mother deliberately broke her 3-month-old daughter’s arm. Upon further investigation, those 39 patients, ages 1 month to 3 years old, had 41 siblings; 12 of those had died suddenly and unexpectedly. [53] The use of covert video, while apparently extremely effective, raises controversy in some jurisdictions over privacy rights.

Legal status[edit]

In most legal jurisdictions, doctors are allowed to give evidence only in regard to whether the child is being harmed. They are not allowed to give evidence in regard to the motive. Australia and the UK have established the legal precedent that FDIA does not exist as a medico-legal entity.

In a June 2004 appeal hearing, the Supreme Court of Queensland, Australia, stated:

As the term factitious disorder (Munchausen’s Syndrome) by proxy is merely descriptive of a behavior, not a psychiatrically identifiable illness or condition, it does not relate to an organized or recognized reliable body of knowledge or experience. Dr. Reddan’s evidence was inadmissible. [54]

The Queensland Supreme Court further ruled that the determination of whether or not a defendant had caused intentional harm to a child was a matter for the jury to decide and not for the determination by expert witnesses:

The diagnosis of Doctors Pincus, Withers, and O’Loughlin that the appellant intentionally caused her children to receive unnecessary treatment through her own acts and the false reporting of symptoms of the factitious disorder (Munchausen Syndrome) by proxy is not a diagnosis of a recognized medical condition, disorder, or syndrome. It is simply placing her within the medical term used in the category of people exhibiting such behavior. In that sense, their opinions were not expert evidence because they related to matters that could be decided on the evidence by ordinary jurors. The essential issue as to whether the appellant reported or fabricated false symptoms or did acts to intentionally cause unnecessary medical procedures to injure her children was a matter for the jury’s determination. The evidence of Doctors Pincus, Withers, and O’Loughlin that the appellant was exhibiting the behavior of factitious disorder (Munchausen syndrome by proxy) should have been excluded. [55]

Principles of law and implications for legal processes that may be deduced from these findings are that:

Any matters brought before a Court of Law should be determined by the facts, not by suppositions attached to a label describing a behavior, i. e., MSBP/FII/FDBP;

MSBP/FII/FDBP is not a mental disorder (i. e., not defined as such in DSM IV), and the evidence of a psychiatrist should not therefore be admissible;

MSBP/FII/FDBP has been stated to be a behavior describing a form of child abuse and not a medical diagnosis of either a parent or a child. A medical practitioner cannot therefore state that a person “suffers” from MSBP/FII/FDBP, and such evidence should also therefore be inadmissible. The evidence of a medical practitioner should be confined to what they observed and heard and what forensic information was found by recognized medical investigative procedures;

A label used to describe a behavior is not helpful in determining guilt and is prejudicial. By applying an ambiguous label of MSBP/FII to a woman is implying guilt without factual supportive and corroborative evidence;

The assertion that other people may behave in this way, i. e., fabricate and/or induce illness in children to gain attention for themselves (FII/MSBP/FDBY), contained within the label is not factual evidence that this individual has behaved in this way. Again therefore, the application of the label is prejudicial to fairness and a finding based on fact.

The Queensland Judgment was adopted into English law in the High Court of Justice by Mr. Justice Ryder. In his final conclusions regarding Factitious Disorder, Ryder states that:

I have considered and respectfully adopt the dicta of the Supreme Court of Queensland in R v. LM [2004] QCA 192 at paragraph 62 and 66. I take full account of the criminal law and foreign jurisdictional contexts of that decision but I am persuaded by the following argument upon its face that it is valid to the English law of evidence as applied to children terms “Munchausen syndrome by proxy” and “factitious (and induced) illness (by proxy)” are child protection labels that are merely descriptions of a range of behaviors, not a pediatric, psychiatric or psychological disease that is identifiable. The terms do not relate to an organized or universally recognized body of knowledge or experience that has identified a medical disease (i. e. an illness or condition) and there are no internationally accepted medical criteria for the use of either reality, the use of the label is intended to connote that in the individual case there are materials susceptible of analysis by pediatricians and of findings of fact by a court concerning fabrication, exaggeration, minimization or omission in the reporting of symptoms and evidence of harm by act, omission or suggestion (induction). Where such facts exist the context and assessments can provide an insight into the degree of risk that a child may face and the court is likely to be assisted as to that aspect by psychiatric and/or psychological expert of the above ought to be self evident and has in any event been the established teaching of leading pediatricians, psychiatrists and psychologists for some while. That is not to minimize the nature and extent of professional debate about this issue which remains significant, nor to minimize the extreme nature of the risk that is identified in a small number of these circumstances, evidence as to the existence of MSBP or FII in any individual case is as likely to be evidence of mere propensity which would be inadmissible at the fact finding stage (see Re CB and JB supra). For my part, I would consign the label MSBP to the history books and however useful FII may apparently be to the child protection practitioner I would caution against its use other than as a factual description of a series of incidents or behaviors that should then be accurately set out (and even then only in the hands of the pediatrician or psychiatrist/psychologist). I cannot emphasis too strongly that my conclusion cannot be used as a reason to re-open the many cases where facts have been found against a carer and the label MSBP or FII has been attached to that carer’s behavior. What I seek to caution against is the use of the label as a substitute for factual analysis and risk assessment. [56]

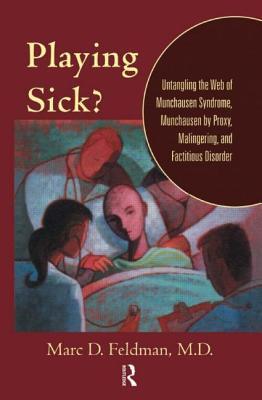

In his book Playing Sick (2004), Marc Feldman notes that such findings have been in the minority among U. S. and even Australian courts. Pediatricians and other physicians have banded together to oppose limitations on child-abuse professionals whose work includes FII detection. [57] The April 2007 issue of the journal Pediatrics specifically mentions Meadow as an individual who has been inappropriately maligned.

In the context of child protection (a child being removed from the custody of a parent), the Australian state of New South Wales uses a “on the balance of probabilities” test, rather than a “beyond reasonable doubt” test. Therefore in the case “The Secretary, Department of Family and Community Services and the Harper Children [2016] NSWChC 3”, the expert testimony of Professor David Isaacs that a certain blood test result was “highly unlikely” to occur naturally or accidentally (without any speculation about motive), was sufficient to refuse the return of the affected child and his younger siblings to the mother. The children had initially been removed from the mother’s custody after the blood test results became known. The fact that the affected child quickly improved both medically and behaviourly after being removed was also a factor. [58]

Notable cases[edit]

Beverley Allitt, a British nurse who murdered four children and injured a further nine in 1991 at Grantham and Kesteven Hospital, Lincolnshire, was diagnosed with Munchausen syndrome by proxy. [59]

Wendi Michelle Scott is a Frederick, Maryland, mother who was charged with sickening her four-year-old daughter. [60]

The book Sickened, by Julie Gregory, details her life growing up with a mother suffering from Munchausen by proxy, who took her to various doctors, coached her to act sicker than she was and to exaggerate her symptoms, and who demanded increasingly invasive procedures to diagnose Gregory’s enforced imaginary illnesses. [61]

Lisa Hayden-Johnson of Devon was jailed for three years and three months after subjecting her son to a total of 325 medical actions – including being forced to use a wheelchair and being fed through a tube in his stomach. She claimed her son had a long list of illnesses including diabetes, food allergies, cerebral palsy, and cystic fibrosis, describing him as “the most ill child in Britain” and receiving numerous cash donations and charity gifts, including two cruises. [62]

In the mid-1990s, Kathy Bush gained public sympathy for the plight of her daughter, Jennifer, who by the age of 8 had undergone 40 surgeries and spent over 640 days in hospitals[63] for gastrointestinal disorders. The acclaim led to a visit with first lady Hillary Clinton, who championed the Bushs’ plight as evidence of need for medical reform. However, in 1996, Kathy Bush was arrested and charged with child abuse and Medicaid fraud, accused of sabotaging Jennifer’s medical equipment and drugs to agitate and prolong her illness. [63] Jennifer was moved to foster care where she quickly regained her health. The prosecutors claimed Kathy was driven by Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy, and she was convicted to a five-year sentence in 1999. [64] Kathy was released after serving three years in 2005, always maintaining her innocence, and having gotten back in contact with Jennifer via correspondence. [65]

In 2014, 26-year-old Lacey Spears was charged in Westchester County, New York, with second-degree depraved murder and first-degree manslaughter. She fed her son dangerous amounts of salt after she conducted research on the Internet about its effects. Her actions were allegedly motivated by the social media attention she gained on Facebook, Twitter, and blogs. She was convicted of second-degree murder on March 2, 2015, [66] and sentenced to 20

Factitious Disorder (Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy)

Overview

What is factitious disorder imposed on another?

In this mental illness, a person acts as if an individual he or she is caring for has a physical or mental illness when the person is not really sick. The adult perpetrator has the diagnosis (FDIA) and directly produces or lies about illness in another person under his or her care, usually a child under 6 years of age. It is considered a form of abuse by the American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children. However, cases have been reported of adult victims, especially the disabled or elderly. FDIA was previously known as Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy.

People with FDIA have an inner need for the other person (often his or her child) to be seen as ill or injured. It is not done to achieve a concrete benefit, such as financial gain. People with FDIA are even willing to have the child or patient undergo painful or risky tests and operations in order to get the sympathy and special attention given to people who are truly ill and their families. Factitious disorders are considered mental illnesses because they are associated with severe emotional difficulties.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5, is the standard reference book for recognized mental illnesses in the United States. It describes this diagnosis to include falsification of physical or psychological signs or symptoms, and induction of illness or injury to another associated with deception. There is no evidence of external rewards and no other illness to explain the symptoms. Fortunately, it is rare (2 out of 100, 000 children).

FDIA most often occurs with mothers—although it can occur with fathers—who intentionally harm or describe non-existent symptoms in their children to get the attention given to the family of someone who is sick. A person with FDIA uses the many hospitalizations as a way to earn praise from others for their devotion to the child’s care, often using the sick child as a means for developing a relationship with the doctor or other health care provider. The adult with FDIA often will not leave the bedside and will discuss in medical detail symptoms and care provided as evidence that he or she is a good caretaker. If the symptoms go away in the hospital, they are likely to return when the caretaker with FDIA is alone with the child or elderly parent.

People with FDIA might create or exaggerate the child’s symptoms in several ways. They might simply lie about symptoms, alter diagnostic tests (such as contaminating a urine sample), falsify medical records, or induce symptoms through various means, such as poisoning, suffocating, starving, and causing infection. The presenting problem may also be psychiatric or behavioral.

How common is factitious disorder imposed on another?

There are no reliable statistics regarding the number of people in the United States who suffer from FDIA, and it is difficult to assess how common the disorder is because many cases go undetected. However, estimates suggest that about 1, 000 of the 2. 5 million cases of child abuse reported annually are related to FDIA.

In general, FDIA occurs more often in women than in men.

Symptoms and Causes

What causes factitious disorder imposed on another?

The exact cause of FDIA is not known, but researchers believe both biological and psychological factors play a role in the development of this disorder. Some theories suggest that a history of abuse or neglect as a child or the early loss of a parent might be factors in its development. Some evidence suggests that major stress, such as marital problems, can trigger an FDIA episode.

What are the symptoms of factitious disorder imposed on another?

Certain characteristics are common in a person with FDIA:

Often is a parent, usually a mother, but can be the adult child of an elderly patient, spouse or caretaker of a disabled adult

Might be a health care professional

Is very friendly and cooperative with the health care providers

Appears quite concerned (some might seem overly concerned) about the child or designated patient

Might also suffer from factitious disorder imposed on self (This is a related disorder in which the caregiver repeatedly acts as if he or she has a physical or mental illness when he or she has caused the symptoms. )

Other possible warning signs of FDIA in children include the following:

The child has a history of many hospitalizations, often with a strange set of symptoms.

Worsening of the child’s symptoms generally is reported by the mother and is not witnessed by the hospital staff.

The child’s reported condition and symptoms do not agree with the results of diagnostic tests.

There might be more than one unusual illness or death of children in the family.

The child’s condition improves in the hospital, but symptoms recur when the child returns home.

Blood in lab samples might not match the blood of the child.

There might be signs of chemicals in the child’s blood, stool, or urine.

Diagnosis and Tests

How is factitious disorder imposed on another diagnosed?

Diagnosing FDIA is very difficult because of the dishonesty that is involved. Doctors must rule out any possible physical illness as the cause of the child’s symptoms, and often use a variety of diagnostic tests and procedures before considering a diagnosis of FDIA.

If a physical cause of the symptoms is not found, a thorough review of the child’s medical history, as well as a review of the family history and the mother’s medical history (many have factitious disorder imposed on self) might provide clues to suggest FDIA. Often, the individual with FDIA may have other comorbid psychiatric disorders. Remember, it is the adult, not the child, who is diagnosed with FDIA. Indeed, the most important or helpful part of the workup is likely to be the review of all old records that can be obtained. Too often, this time-consuming but critical task is forgotten and the diagnosis is missed. Physicians will ask Children’s Services, and the Legal Department for assistance in reviewing the facts.

Management and Treatment

How is factitious disorder imposed on another treated?

The first concern in cases of FDIA is to ensure the safety and protection of any real or potential victims. This might require that the child be placed in the care of another. In fact, managing a case involving FDIA often requires a team that includes social workers, foster care organizations, and law enforcement, as well as the health care providers.

Successful treatment of people with FDIA is difficult because those with the disorder often deny there is a problem. In addition, treatment success is dependent on catching the person in the act or the person telling the truth. People with FDIA tend to be such accomplished liars that they begin to have trouble telling fact from fiction.

Psychotherapy (a type of counseling) generally focuses on changing the thinking and behavior of the individual with the disorder (cognitive-behavioral therapy). The goal of therapy for FDIA is to help the person identify the thoughts and feelings that are contributing to the behavior, and to learn to form relationships that are not associated with being ill.

What are the complications of factitious disorder imposed on another?

This disorder can lead to serious short- and long-term complications, including continued abuse, multiple hospitalizations, and the death of the victim. (Research suggests that the death rate for victims of FDIA is about 10 percent. ) In some cases, a child victim of FDIA learns to associate getting attention to being sick and develops factitious disorder imposed on self. Considered a form of child abuse, FDIA is a criminal offense.

Prevention

Can factitious disorder imposed on another be prevented?

There is no known way to prevent this disorder. However, it might be helpful to begin treatment in people as soon as they begin to have symptoms. Removing the child or other victim from the care of the person with FDIA can prevent further harm to the victim.

Outlook / Prognosis

What is the prognosis (outlook) for people with factitious disorder imposed on another?

Generally, FDIA is a very difficult disorder to treat and often requires years of therapy and support. Social services, law enforcement, children’s protective services, and physicians must function as a team to stop the behavior.

Munchausen Syndrome By Proxy – familydoctor.org

What is Munchausen syndrome by proxy?

Munchausen syndrome by proxy (MSP) is a mental illness. It is also a form of child abuse. It affects caregivers, especially caregivers of children. It is also known as factitious disorder by proxy. Mothers of small children are most often affected by this condition. Fathers or other caregivers can have it as well.

Someone suffering from MSP will act as though the person under his or her care is sick. They often will falsify medical information. They may lie to medical professionals about the health or condition of the person in their care. They do this to gain sympathy or for attention.

Someone who has MSP may purposely take action to make their child sick. They knowingly will expose the child to painful or risky medical procedures, even surgeries. They may deliberately create symptoms in a child. They can do this by withholding food, poisoning or suffocating the child, giving the child inappropriate medicines, or withholding prescribed medicines. Creating these situations can put the child at extreme risk.

Common illnesses or symptoms that caregivers take MSP victims to the doctor for include:

Failure to thrive

Nausea and vomiting

Diarrhea

Seizures

Breathing difficulty and asthma

Infections

Allergic reactions

Fevers of unknown origins

Other illnesses that require immediate emergency care

Those with MSP are not discouraged by the cost of medical treatments. They don’t worry about how they will manage the bills. Instead, they believe driving up a large hospital bill reinforces the perception that they are doing everything they can for their child. They think others will see them as even better caretakers.

What are the symptoms of Munchausen syndrome by proxy?

Symptoms that can help identify someone who has MSP can be hard to spot. There are certain personality traits and backgrounds that seem to be common. Many suffered mental, physical, or sexual abuse growing up. Or they received love or attention only when they were sick.

As adults, people with MSP are very interested in medicine. They often work in the medical field. They can speak expertly about medical conditions. They are typically very cooperative and friendly with health care professionals. They always appear to be completely devoted to the well being of their child.

But to fake symptoms of illness in their child, they may do extreme things. These could include:

Giving the child certain medicines or substances that will make them throw up or have diarrhea

Heating up thermometers so it looks like the child has a fever

Not giving the child enough to eat so it looks like they can’t gain weight

Adding blood to the child’s urine or stool

Making up lab results

In the child, symptoms of a caregiver with MSP include a history of being in and out of hospitals with unusual health symptoms. Many times, their symptoms do not match any single disease. Symptoms usually get worse when they are alone with their caregiver. Symptoms often disappear in the absence of that person.

What causes Munchausen syndrome by proxy?

Doctors don’t know what causes this mental illness. It may be the result of being abused as a child. Some people with MSP may also have Munchausen syndrome. This is where they fake illness for themselves to gain attention.

How is Munchausen syndrome by proxy diagnosed?

The ethical issues involved in MSP make it hard to diagnose. Accusing a mother, father, or caretaker of intentionally creating symptoms or making a child sick is a serious matter. Medical professionals will look for symptoms and other incriminating evidence before doing so.

One way to confirm suspicions of MSP is to separate the mother, father, or caregiver from the child, then see if the child’s symptoms improve. Doctors also can evaluate medical records. They can look for patterns that suggest something is off. For example, a child who has been seen for many different illnesses during a short period of time should trigger suspicion. If MSP is suspected, health care providers are required to report it.

Can Munchausen syndrome by proxy be prevented or avoided?

Unfortunately, there is no way to prevent MSP. The caregiver must recognize that his or her feelings about illness are not normal. In those situations, seeking help could prevent them from harming a child.

It is usually up to others to recognize the behavior and stop it before it escalates. If you believe a child is in danger or is currently a victim of MSP, contact a health care professional, the police, or child protective services.

Munchausen syndrome by proxy treatment

Safety of the child is the No. 1 priority of treatment. The child should be treated for any medical problems they are having and protected from further abuse. They may need to be removed from the care of the affected caregiver. Psychological treatment may be necessary as the child recovers.

Treatment of the mother, father, or caregiver involved is not as straightforward. Many times, this person will deny playing a role, even when evidence proves it. They often have blurred what is true and what is not. Until they are ready to recognize the truth, it will be difficult for them to get better.

Psychotherapy is recommended for persons who have MSP. During these counseling sessions, the therapist helps the caregiver identify the feelings that caused his or her harmful behavior. Over time, the caregiver can learn to change that behavior. They can learn to form healthy relationships that don’t rely on someone being sick.

Because this is a form of child abuse, the syndrome must be reported to the authorities.

Living with Munchausen syndrome by proxy

Someone living with Munchausen syndrome by proxy has a serious mental illness. It is a form of child abuse. So they cannot be allowed to continue their behavior. If you suspect someone you know has this illness, it is important that you notify a health care professional, the police, or child protective services. Call 911 if you know a child who is in immediate danger because of abuse or neglect.

You can also call the Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline at 1-800-4-A-CHILD (1-800-422-4453). Crisis counselors are available to help you figure out next steps. All calls are anonymous and confidential.

Questions to ask your doctor

What are some clues that my spouse/child’s caregiver has Munchausen syndrome by proxy?

What could be causing my spouse/child’s caregiver to act this way?

What should I do if I suspect someone I know is showing symptoms of Munchausen syndrome by proxy?

Can someone fully recover from Munchausen syndrome by proxy?

Frequently Asked Questions about munchausen syndrome by proxy wiki

What is Munchausen syndrome by proxy?

Factitious disorder imposed on another (FDIA) formerly Munchausen syndrome by proxy (MSP) is a mental illness in which a person acts as if an individual he or she is caring for has a physical or mental illness when the person is not really sick.Nov 26, 2014

What are the symptoms of Munchausen syndrome by proxy?

Munchausen syndrome by proxy (MSP) is a mental illness….Common illnesses or symptoms that caregivers take MSP victims to the doctor for include:Failure to thrive.Nausea and vomiting.Diarrhea.Seizures.Breathing difficulty and asthma.Infections.Allergic reactions.Fevers of unknown origins.More items…•Jan 25, 2021

Why was Munchausen by proxy renamed?

The term refers to the circumstance where the child is the subject of the fabrication of an illness by the parent. It was thought that the parent ‘with MSbP’ was motivated by trying to gain attention from medical professionals by inducing or fabricating the sickness in their child.Sep 23, 2005